fig 1a

fig 2c

fig 2d

fig 4a

fig 4b

fig 4c

fig 5c

Carmen Ravanelli Guidotti

Since late Middle Ages, abundance of raw material and specific cultural situations gave life, along the whole Italian peninsula, to several districts of majolica featuring a production capability so specialized to compete with the majorica, painted in lustro technique, developed in the Spanish centres of Valentia area, and to which they were able to oppose an increasingly craft of very high level technique and an even more refined taste, up to turning majolica into a luxury ceramic product.

Since early 16th century, in decorative repertoires it is the storiated decoration that represents the trump either for prestige and value, through which the workshops, thanks to their production decorated with sumptuous figures, may meet the magnificence of the Courts and so “the eyes of Princes” who “competed for it paying a fortune.” Even, “at the time, there were sovereigns so lover of arts, that did not disdain to exercise the practice of potter; and if they wanted to cement their mutual friendship with presents, they made them in majolica or half majolica from their own areas; because they tried to hire artists to introduce and maintain it.

Therefore, we see the Estensi giving presents to the Gonzaga, Costanza Sforza di Pesaro to Pope Sisto IV, Roberto Malatesta to Lorenzo il Magnifico, and Giudobaldo II Della Rovere to Philip II of Spain,” and, not last, to eminent cardinals.

In the first half of the century, the primacy is steadily in the hand of the workshops from Metauro area (Casteldurante, Urbino, Pesaro), that outstand for their blazoned and polychrome storiated works. They are able to produce prominent dinner services, painted “in lands, tales and stories” to make presents to important figures, but also for historical banquets, in which ceramics plays a state role and celebrates the historical, political and social pride of a family.

For example, for the Pucci, a noble Florentine family, two wonderful storiated “credenze” (services of dishes) were made in Urbino: one, of which at present we are aware of the 37 pieces hosted in several museums and private collections, painted between 1532 and 1533 by Francesco Xanto Avelli, pictor egregius of majolica; the other (fig. 1a), was made for Antonio Pucci (1485–1544), bishop of Pistoia, Vannes (France), Albano and Sabina, created cardinal by Clemente VII Medici in 1531 and unexpectedly dead in Bagnoregio on 12 October 1544.

There are twelve dishes of this set left to date; hosted in some of the most important museums of the world, nine are decorated with profane scenes (Mars and Venus, Leda and the swan, Hercules and Cacus, Pyramus and Thisbe, Perillus, Vulcan with Venus and Mars, Cadmus, Peleus and Thetis, Saturn on the horse), one featuring a roman history scene (Mucius Scaevola), and two with sacred histories (The Finding of Moses and Angels visiting Abraham). Up to date, the specialist literature dated this before 1544, namely before the cardinal’s death. But the finding of a dish, in a private collection, nearly twin to another of the same set hosted now at British Museum in London, dated “1544” on the verso, gives us an unquestionable chronological reference, therefore this is a masterpiece of the prestigious “credenza” for Antonio Pucci, also confirmed by the coat of arms on the plates. So, it was made the same year of the death of the cardinal: this coincidence happened also in 1535 for the service for Cardinal Antonio Duprat, made in Guido Durantino’s workshop in Urbino and that shows the same date of the death of the august French prelate.

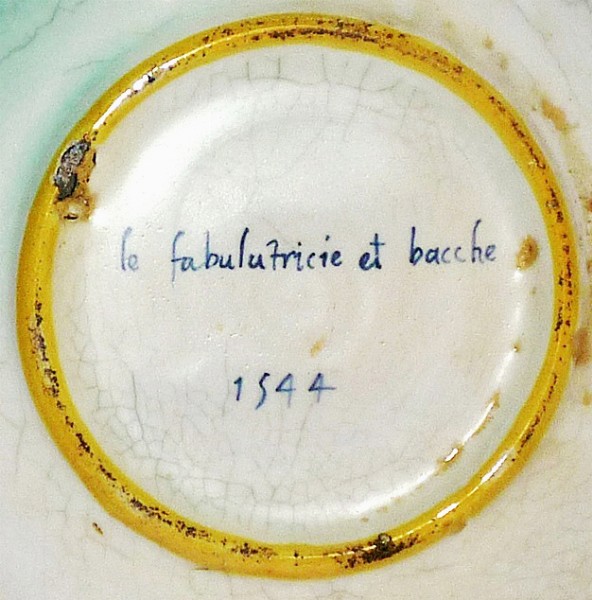

Like the plate in London, also this one – on the full surface on recto – shows the story from Ovid, Book IV, of the three daughters (Leucippe, Alsippe and Alcithoe) of Minyas, a gentleman from Thebes; the three daughters, instead of following the Bacchic joys, remained at home weaving wool. During their work, they tell stories (very famous are those of Pyramus and Thisbe and Salmacis and Hermaphroditus), as per the legend on the verso of the plate “le fabulatricie de bacche / 1544” (the fabulists of Bacchus / 1544), so Jupiter punishes and transforms them into bats (Ovid, Metamorphoses, IV, 32-415). The detail on the side recalls a bucolic evocation: Bacchus, recognizable under the crown decorated with wine leafs around his head, portrayed like a shepherd with his herd, seated in front of a cavern, with his left hand holds a bagpipe, according to an iconography that in the storiated majolica looks like the one of Orpheus enchanting the animals.

From a stylistic point of view, both versions are ascribed to the same author, also for the handwriting that features both legends, with the single variable of the de, which separates the words fabulatrici and bacche, which in our plate could rather look like an et (fig. 1b), but that in the British Museum version is clearly a de (fig. 1c).

The painter is one of those anonymous personalities who worked at the Fontana’s workshop during the 1540s, namely in his full productive maturity, the one in which the works in general show a good balance between the figurative and the landscape masses, an elegant floating movement of the draperies, a brilliant chromatic quality, an harmonious movement of poses and figures; all those elements increasing the sense of fabula.

Anyway, he is a master who is very close to the head of the workshop, Guido Durantino Fontana, even imitating his handwriting of the legends. Also the iconography reflects that fruitful period of the well-known workshop from Urbino, and in general of Italian workshops that were able to produce storiated works, in which engraving repertoires were used to compose the different scenes by bringing close different graphic sources, from which the pounces were derived. It is a practice confirmed also in this case, in which the three figures of the daughters of Mynias are represented copying as many figures as those contained in the famous print by Jacopo Caraglio (from Rosso Fiorentino), that shows La gara tra le Muse e le Pieridi (The contest between the Muses and the Pieridis) (fig. 1d).

Another beautiful example of majolica intended to “aristocratic flats” is a cup with Pepoli coat of arms (fig. 2a), whose heraldic identification is confirmed by the Fire Phoenix, of which the Bolognese noble family crest could be featured, here placed on top of a temple according to Bramante style: an architectonic module that will be repeated in 1547 in a similar way on another cup, from a private collection, representing Postumia, with the coat of arm of Bosio Sforza and Costanza Farnese, by Francesco Durantino.

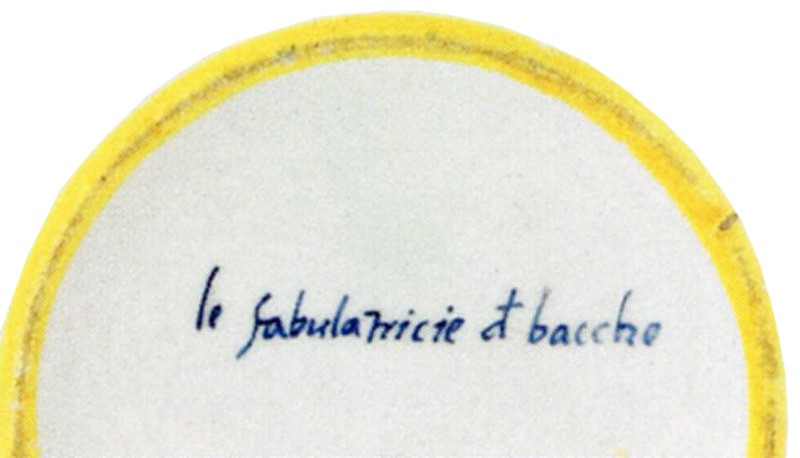

The work is proud of its collectors’ descent, having been part of the collection of Achillito Chiesa and Agosti-Mendoza, and it is recalled by G.V. Norman who publishes another one, housed at Wallace Collection, as well featured by the Pepoli coat of arms and the Phoenix placed in the foliage of a tree, portraying Mucius. The legend is shown in the capital letter, whereas the one on Alessandro cup shows a light calligraphy, with wide letters and to some extent at a distance one from the other (fig. 2b), that can be find also in other works, of the same period, from Urbino.

The Pepoli cup completely reveals the taste for historic or profane themes inspired by Latin authors, such as Ovid, Valerius Maximus, Livy, and so on. Also Plutarch becomes one of the authors that gained great favour by Humanism, known after his successful vulgar editions, like the one of Niccolò Zoppino printed in Venice in 1525. This is proved by the legend on the verso of this cup, namely “Alisandro che / se fe patron de / lasia” (Alexander master of Asia), taken out from a passage of the Parallel Lives by the Greek historian.

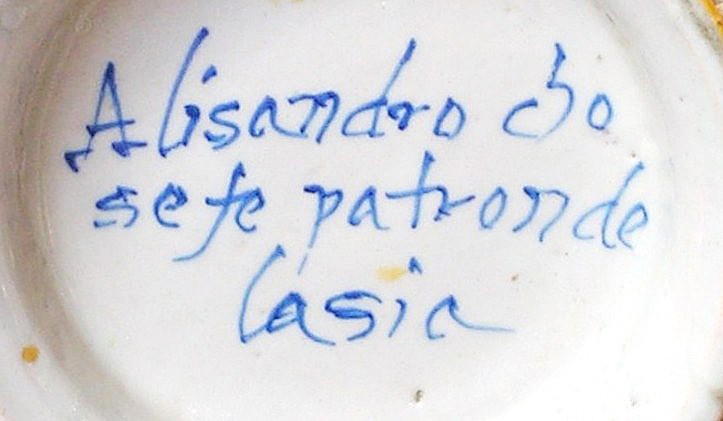

On the contrary, the iconographic feature depends on the transcripts of engraving sources very in fashion on the first half of the 16th century in the majolica workshops, especially those from Urbino, developed with great talent and originality, such as the mythical chariot of Gordias – here embellished with wonderful lion masks – placed in the centre of the composition to divide two masses of characters: one, on the left, headed by a young Alexander, ichnographically taken out from the figure of St. Michael engraved by Marcantonio Raimondi (figg. 2c, d), the other, on the opposite side, shows the chiefs of the beaten enemies. Overall, the work stands out for its balanced compositional structure and for the light grace and the good drawing that feature the figures, all elements that can be traced back to Guido Durantino’s workshop, around 1535–1540.

For another cardinal, again in Urbino, a wonderful soup plate (fig. 3a) was made: in the middle, the arms of cardinal Girolamo Rusticucci (1537–1603) stand out in a medallion framed by a continuous narrative wide band that, with undisputable and peculiar optical effect, spins around the medallion itself and contains a view of a city with towers, sloping roofed houses, domes, bridge, barrel vaults, characters busy at their rural works and so on. All made in blue monochrome, with marked white heightening on a berettino light blue. The magnificent decorative apparatus is completed by a narrow band with raffaellesche, that house tiny and graceful fantasy figurines, birds, small cages, masks, harpies, tablets, dragons, vases and varied phytomorphic details made with a refined and lively calligraphic quality, typical to the raffaellesca from Urbino of the 1560s.

In the Rusticucci soup plate is no less interesting the verso, embellished with “a canestro” (canister) or “a corolla” decorations, a motif composed by cuspidate and intersected petals, pertaining to a typology that, according to what in vogue at the time, in the 16th century was defined “alla veneziana” (Venetian style) (fig. 3b). On the other hand, it is a decorative choice in line with the berettino light blue background, a quite refined technique and pride of the Venetian workshops, that gave a sophisticated aura to the final result of the compositions on majolica, especially the storiated ones.

The attribution of Rusticucci’s plate to the Antonio Patanazzi’s workshop from Urbino is based considering different points of view. For sure the stylistic one, that shows peculiarities especially in the landscape workmanship; style that now the critics mainly ascribe to the well-known workshop from Urbino, that was offered either on berettino enamel and the more “legitimate” polychrome.

Moreover, in literature, it is now clear how, in the huge production of this workshop, from around 1580, the enamel technique on berettino light blue background was a deep-seeded practice.

In a contract referred to his workshop, dated 1585, among other objects, several light blue background enamel majolica were recorded and among others there was a “bacile bertino” (small berettino washbasin), perhaps something similar to our soup plate. But, in other documents it is reported also a deep blue “credenza” and varied majolica decorated according to “Venetian style”; archive sources which find evidences in numerous finds, especially referable to works from Patanazzis workshop, painted either in the genre of storiated and in landscape like, found in Pesaro or in the vaults of Palazzo Ducale in Urbino. Also the provenance of the client of the work – Girolamo Rusticucci – supports the attribution of this work to the circle from Urbino. Born in Cartoceto, a small town of the Ducato di Urbino, now in the province of Pesaro and Urbino, in June 1570 acceded the cardinal title and in the same month was appointed bishop of Senigallia. Influential figure of prelate in the Marches, perhaps honoured with this refined gift, that in the centre shows his coat of arms, completed on the sides with the typical cardinal tassels; heraldic affiliation that is confirmed by his coat of arms put either on paper documents and on the sides of his engraved portrait.

With works like those mentioned above, it is demonstrated how much majolica was at the same level of other decorative arts, especially when able to convey, with its shiny and glassy colours, the themes of the great Manneristic painting spread by the engraving repertoires. After the dominant Raphael’s current, from mid-16th century the refined and erudite Mannerism of Battista Franco and Zuccaris becomes popular: mannerism that, in the shape of drawing or drawing study from 1560, enters in the workshops of Urbino, so that the profane taste and the recalling of the ancient tales of the historical-celebratory painting are splendidly transposed especially on the grand-ducal “credenze”, to the extent that these majolica “di terre vulgari, di non vulgare artifizio” (from vulgar lands, but not vulgar in ability) from then on achieve the status of material worthy of “a diletto e pompa dei principi” (the delight and the pomp of princes) and stand out in the first Italian majolica collection as “oggetti della meraviglia degli occhi più erudite” (objects for the astonishment of the most erudite eyes).

At the same time of the Marches district, also the one from Romagna was looking for its affirmation. Faenza is the leader, and from decades now, is a specialized centre in the production of majolica. Faenza is not a Court, so it relies on its Cento Pacifici and on the innate inclination of the mercantile activities to be able to propose “di qua et là per l’Italia” (here and there in Italy) and in Europe its majolica.

From 1530s, Faenza workshops try to compete with the Marches ones with their very refined “vaghezze” (vagueness) and “gentilezze” (graces) painted on light blue berettino enamel, framing the blazoned services with the arms of Gonzaga, Este, Pio da Carpi Guicciardini-Salviati, and so on, even if the supremacy up to mid-16th century is still in the hands of the craftsman of Marches districts. Its workshops, melting pot of experimentations, fully interpret the widespread desire of novelty thanks to a lively, immediate painting, made with few chromatic touches (deep blue, yellow, orange) on the surface now “bianche e polite” (white and clean) of a technically perfect enamel. It is a unique style, a successful novelty, in which mannerist inflexions and baroque attitudes lively become part of the rediscovered taste of making majolica: the figure scene, the allegory, the heraldic theme, themes always recurring in majolica making inspiration, acquire importance in the freedom of a new Compendiario style, as per the classical Pompeian memory.

The circle of potential clients for parade services, often with the arm, besides the princely tables, increased thanks to the anoblissement of families whose origin was mercantile or bourgeois, that liked also the white, the predominant colour, which enhanced the shapes, sometimes wavy and hull shaped, also defined as “smartellate” (hummered) or “abborchiate” (studded), especially “cavate dagli argenti” (from the silvers) e that met the most updated trends.

Heraldic study of the “whites” of Faenza described a picture of continuous trading, a lively network of families and marriage relationships as well as relationships with Church high hierarchies that played an essential role in the economic fortune of the majolica from Faenza.

So, monumental “credenze” were made with these “whites”; these soon entered in competition with the polychrome storiated ones from Urbino, in which the most organized and important workshops from Faenza excelled: those from Francesco Mezzarisa, Virgilotto Calamelli, from the Bettisis and Utilis, who, thanks to the “whites” gave life to a wide movement that renovated the Renaissance tradition that was on the decline.

Among the first clients there were the noble local families who were active and steady intermediary for improving relationships beyond their territory – at the beginning oriented towards the near rich centre of Bologna – rapidly extended to the whole region, from Parma to Rimini therefore to all the Italian aristocracy: Gonzaga, Este, Medici, Farnese, Orsini, Aldobrandini, Pallavicini, Altieri, and so on.

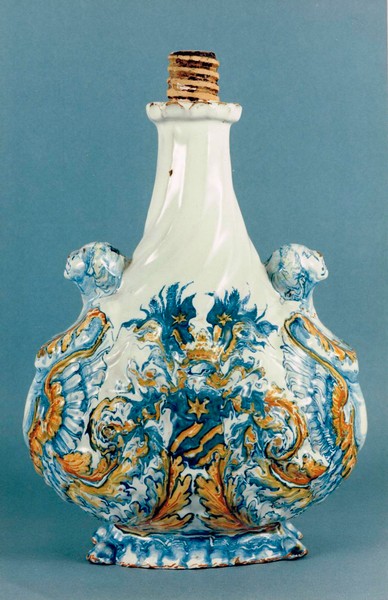

A flask with Malipiero coat of arms (figg. 4a, b), marked in its unmistakable heraldic figure shown through the coats of arms “d’armi e d’insegne” (of arms and insignia) of the time (fig. 4b), testifies for example how, in the second half of 16th century, Venetian nobles, even they had magnificent polychrome storiated majolica made by the productive local workshop of master Domenico, also appreciated the white “credenze” from Faenza.

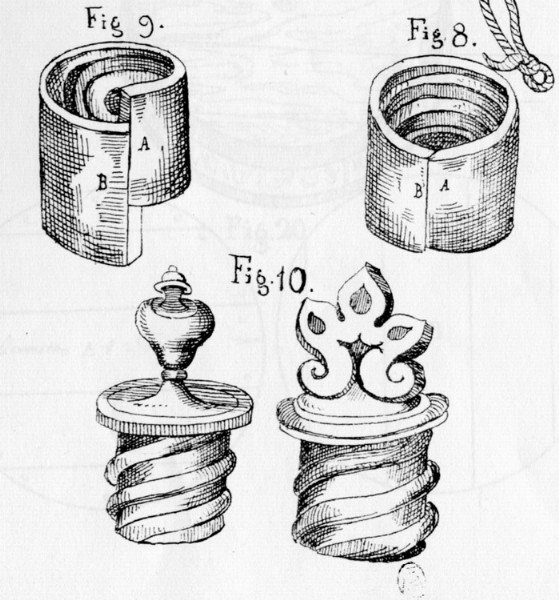

The flask shows on sides two modelled harpies, whose outstretched heads offer sufficient thickness to host the hole for the rope. So, it pertains to the so-called genre “da pellegrino” (pilgrim style), a style that in the shaped surface fits to the embossed silver or copper models; a plastic effect that to some extent is absorbed by the waxy and coating quality of the enamel of the “white” from Faenza, very appealing to the touch. This style is also certified in models featured by prestigious coats of arms painted on both sides, among which, it is worth remembering the flasks for the service of Albert V of Bavaria, made around 1576 by the Bettisis workshop and for the most part housed in the Residenz Museum in Munich. Flasks featured by screw stoppers, such as this one for the Malipieros, or, just mentioning Piccolopasso with the “bocca a vite ad uso delle fiasche di argento” (screw mouth in use for the silver flasks) (fig. 4c), that the workshop itself includes also in the prestigious “credenze” for the Medici and Gonzaga families.

In transalpine countries, the Wittelsbachs are the privileged clients of the Bettisis from Faenza, and for them, in 1590, two services delivered to “the Duke of Bavaria” are reported. The Duke was Wilhelm V, who certainly was familiar and appreciated Italian majolica, having received as a gift from the Duke of Urbino, Francesco Maria della Rovere, a “credenza” made by the Fontana, the most important workshop in Urbino.

These prestigious Bavarian orders opened the way to this workshop to other wealthy commissions, especially in the South of Germany. A large bowl (figg. 5a, b) modelled in “baccellature” according to the silvers style, called “a gran costole” (large ribs), dateable to 1575–1580, was chosen to celebrate another family in the same region, the Unterholzer. Their coat of arms, decorated with lambrequins and two flashy half wings, stands out in the centre of a decoration featured by a delicate and lively ductus compendiario; the presence of two rhomboidal medallions that contain one feminine bust and one masculine bust, arranged according the “old style”, suggest the idea of a nuptial gift, seemingly confirmed by the presence of two allegorical figures, the Fortress and, perhaps, also the Prudence. Most probably it was about a supply that included also the majolica in different styles, given the existence of a flask of the already mentioned style “da pellegrino” (fig. 5c), on which the same coat of arm of the noble Bavarian family is painted.

The culture of the “whites” from Faenza, especially in the shapes of majolica, fully and lively understands the passage from Mannerism to Baroque, as per the opulent structure of its shapes, often embossed, in a plastic role of the modelled parts, accessory to the object functionality, with sphinxes, caryatids, harpies, putti, leonine or caprine legs and so on, made through plaster moulds, according to the criteria of pre-industrial serial reproducibility.

In this way, the small town from Romagna was able to tie forever its name to the fortune of its majolica and, for a century and a half, in the western world the combination Faenza-faïence ruled, up to the appearance of the European porcelain in the early 18th century. But the fortune of these works in majolica will go on thanks to the masterpieces produced by “these manufactures, since then, spread out all around Europe”, that luckily survived to the present day and that “can be admired in the private room as marvels of art”: a matter that opens on the great and fascinating theme of collecting Italian majolica, that in the future will deserve other pages of analysis.

Acknowledgments

Materials and information were generously given by: Giovanni Asioli Martini, Paolo Baccherini, Enrico Caviglia, Silvia Glaser, Johanna Lessmann, Gustav Pfeifer.

Notice

Works at figs. 2 and 5 are further developed in an essay for the catalogue of the exhibition “Prima del Made in Italy” (Before Made in Italy), in press.

Since late Middle Ages, abundance of raw material and specific cultural situations gave life, along the whole Italian peninsula, to several districts of majolica featuring a production capability so specialized to compete with the majorica, painted in lustro technique, developed in the Spanish centres of Valentia area, and to which they were able to oppose an increasingly craft of very high level technique and an even more refined taste, up to turning majolica into a luxury ceramic product.

Since early 16th century, in decorative repertoires it is the storiated decoration that represents the trump either for prestige and value, through which the workshops, thanks to their production decorated with sumptuous figures, may meet the magnificence of the Courts and so “the eyes of Princes” who “competed for it paying a fortune.” Even, “at the time, there were sovereigns so lover of arts, that did not disdain to exercise the practice of potter; and if they wanted to cement their mutual friendship with presents, they made them in majolica or half majolica from their own areas; because they tried to hire artists to introduce and maintain it.

Therefore, we see the Estensi giving presents to the Gonzaga, Costanza Sforza di Pesaro to Pope Sisto IV, Roberto Malatesta to Lorenzo il Magnifico, and Giudobaldo II Della Rovere to Philip II of Spain,” and, not last, to eminent cardinals.

In the first half of the century, the primacy is steadily in the hand of the workshops from Metauro area (Casteldurante, Urbino, Pesaro), that outstand for their blazoned and polychrome storiated works. They are able to produce prominent dinner services, painted “in lands, tales and stories” to make presents to important figures, but also for historical banquets, in which ceramics plays a state role and celebrates the historical, political and social pride of a family.

For example, for the Pucci, a noble Florentine family, two wonderful storiated “credenze” (services of dishes) were made in Urbino: one, of which at present we are aware of the 37 pieces hosted in several museums and private collections, painted between 1532 and 1533 by Francesco Xanto Avelli, pictor egregius of majolica; the other (fig. 1a), was made for Antonio Pucci (1485–1544), bishop of Pistoia, Vannes (France), Albano and Sabina, created cardinal by Clemente VII Medici in 1531 and unexpectedly dead in Bagnoregio on 12 October 1544.

There are twelve dishes of this set left to date; hosted in some of the most important museums of the world, nine are decorated with profane scenes (Mars and Venus, Leda and the swan, Hercules and Cacus, Pyramus and Thisbe, Perillus, Vulcan with Venus and Mars, Cadmus, Peleus and Thetis, Saturn on the horse), one featuring a roman history scene (Mucius Scaevola), and two with sacred histories (The Finding of Moses and Angels visiting Abraham). Up to date, the specialist literature dated this before 1544, namely before the cardinal’s death. But the finding of a dish, in a private collection, nearly twin to another of the same set hosted now at British Museum in London, dated “1544” on the verso, gives us an unquestionable chronological reference, therefore this is a masterpiece of the prestigious “credenza” for Antonio Pucci, also confirmed by the coat of arms on the plates. So, it was made the same year of the death of the cardinal: this coincidence happened also in 1535 for the service for Cardinal Antonio Duprat, made in Guido Durantino’s workshop in Urbino and that shows the same date of the death of the august French prelate.

Like the plate in London, also this one – on the full surface on recto – shows the story from Ovid, Book IV, of the three daughters (Leucippe, Alsippe and Alcithoe) of Minyas, a gentleman from Thebes; the three daughters, instead of following the Bacchic joys, remained at home weaving wool. During their work, they tell stories (very famous are those of Pyramus and Thisbe and Salmacis and Hermaphroditus), as per the legend on the verso of the plate “le fabulatricie de bacche / 1544” (the fabulists of Bacchus / 1544), so Jupiter punishes and transforms them into bats (Ovid, Metamorphoses, IV, 32-415). The detail on the side recalls a bucolic evocation: Bacchus, recognizable under the crown decorated with wine leafs around his head, portrayed like a shepherd with his herd, seated in front of a cavern, with his left hand holds a bagpipe, according to an iconography that in the storiated majolica looks like the one of Orpheus enchanting the animals.

From a stylistic point of view, both versions are ascribed to the same author, also for the handwriting that features both legends, with the single variable of the de, which separates the words fabulatrici and bacche, which in our plate could rather look like an et (fig. 1b), but that in the British Museum version is clearly a de (fig. 1c).

The painter is one of those anonymous personalities who worked at the Fontana’s workshop during the 1540s, namely in his full productive maturity, the one in which the works in general show a good balance between the figurative and the landscape masses, an elegant floating movement of the draperies, a brilliant chromatic quality, an harmonious movement of poses and figures; all those elements increasing the sense of fabula.

Anyway, he is a master who is very close to the head of the workshop, Guido Durantino Fontana, even imitating his handwriting of the legends. Also the iconography reflects that fruitful period of the well-known workshop from Urbino, and in general of Italian workshops that were able to produce storiated works, in which engraving repertoires were used to compose the different scenes by bringing close different graphic sources, from which the pounces were derived. It is a practice confirmed also in this case, in which the three figures of the daughters of Mynias are represented copying as many figures as those contained in the famous print by Jacopo Caraglio (from Rosso Fiorentino), that shows La gara tra le Muse e le Pieridi (The contest between the Muses and the Pieridis) (fig. 1d).

Another beautiful example of majolica intended to “aristocratic flats” is a cup with Pepoli coat of arms (fig. 2a), whose heraldic identification is confirmed by the Fire Phoenix, of which the Bolognese noble family crest could be featured, here placed on top of a temple according to Bramante style: an architectonic module that will be repeated in 1547 in a similar way on another cup, from a private collection, representing Postumia, with the coat of arm of Bosio Sforza and Costanza Farnese, by Francesco Durantino.

The work is proud of its collectors’ descent, having been part of the collection of Achillito Chiesa and Agosti-Mendoza, and it is recalled by G.V. Norman who publishes another one, housed at Wallace Collection, as well featured by the Pepoli coat of arms and the Phoenix placed in the foliage of a tree, portraying Mucius. The legend is shown in the capital letter, whereas the one on Alessandro cup shows a light calligraphy, with wide letters and to some extent at a distance one from the other (fig. 2b), that can be find also in other works, of the same period, from Urbino.

The Pepoli cup completely reveals the taste for historic or profane themes inspired by Latin authors, such as Ovid, Valerius Maximus, Livy, and so on. Also Plutarch becomes one of the authors that gained great favour by Humanism, known after his successful vulgar editions, like the one of Niccolò Zoppino printed in Venice in 1525. This is proved by the legend on the verso of this cup, namely “Alisandro che / se fe patron de / lasia” (Alexander master of Asia), taken out from a passage of the Parallel Lives by the Greek historian.

On the contrary, the iconographic feature depends on the transcripts of engraving sources very in fashion on the first half of the 16th century in the majolica workshops, especially those from Urbino, developed with great talent and originality, such as the mythical chariot of Gordias – here embellished with wonderful lion masks – placed in the centre of the composition to divide two masses of characters: one, on the left, headed by a young Alexander, ichnographically taken out from the figure of St. Michael engraved by Marcantonio Raimondi (figg. 2c, d), the other, on the opposite side, shows the chiefs of the beaten enemies. Overall, the work stands out for its balanced compositional structure and for the light grace and the good drawing that feature the figures, all elements that can be traced back to Guido Durantino’s workshop, around 1535–1540.

For another cardinal, again in Urbino, a wonderful soup plate (fig. 3a) was made: in the middle, the arms of cardinal Girolamo Rusticucci (1537–1603) stand out in a medallion framed by a continuous narrative wide band that, with undisputable and peculiar optical effect, spins around the medallion itself and contains a view of a city with towers, sloping roofed houses, domes, bridge, barrel vaults, characters busy at their rural works and so on. All made in blue monochrome, with marked white heightening on a berettino light blue. The magnificent decorative apparatus is completed by a narrow band with raffaellesche, that house tiny and graceful fantasy figurines, birds, small cages, masks, harpies, tablets, dragons, vases and varied phytomorphic details made with a refined and lively calligraphic quality, typical to the raffaellesca from Urbino of the 1560s.

In the Rusticucci soup plate is no less interesting the verso, embellished with “a canestro” (canister) or “a corolla” decorations, a motif composed by cuspidate and intersected petals, pertaining to a typology that, according to what in vogue at the time, in the 16th century was defined “alla veneziana” (Venetian style) (fig. 3b). On the other hand, it is a decorative choice in line with the berettino light blue background, a quite refined technique and pride of the Venetian workshops, that gave a sophisticated aura to the final result of the compositions on majolica, especially the storiated ones.

The attribution of Rusticucci’s plate to the Antonio Patanazzi’s workshop from Urbino is based considering different points of view. For sure the stylistic one, that shows peculiarities especially in the landscape workmanship; style that now the critics mainly ascribe to the well-known workshop from Urbino, that was offered either on berettino enamel and the more “legitimate” polychrome.

Moreover, in literature, it is now clear how, in the huge production of this workshop, from around 1580, the enamel technique on berettino light blue background was a deep-seeded practice.

In a contract referred to his workshop, dated 1585, among other objects, several light blue background enamel majolica were recorded and among others there was a “bacile bertino” (small berettino washbasin), perhaps something similar to our soup plate. But, in other documents it is reported also a deep blue “credenza” and varied majolica decorated according to “Venetian style”; archive sources which find evidences in numerous finds, especially referable to works from Patanazzis workshop, painted either in the genre of storiated and in landscape like, found in Pesaro or in the vaults of Palazzo Ducale in Urbino. Also the provenance of the client of the work – Girolamo Rusticucci – supports the attribution of this work to the circle from Urbino. Born in Cartoceto, a small town of the Ducato di Urbino, now in the province of Pesaro and Urbino, in June 1570 acceded the cardinal title and in the same month was appointed bishop of Senigallia. Influential figure of prelate in the Marches, perhaps honoured with this refined gift, that in the centre shows his coat of arms, completed on the sides with the typical cardinal tassels; heraldic affiliation that is confirmed by his coat of arms put either on paper documents and on the sides of his engraved portrait.

With works like those mentioned above, it is demonstrated how much majolica was at the same level of other decorative arts, especially when able to convey, with its shiny and glassy colours, the themes of the great Manneristic painting spread by the engraving repertoires. After the dominant Raphael’s current, from mid-16th century the refined and erudite Mannerism of Battista Franco and Zuccaris becomes popular: mannerism that, in the shape of drawing or drawing study from 1560, enters in the workshops of Urbino, so that the profane taste and the recalling of the ancient tales of the historical-celebratory painting are splendidly transposed especially on the grand-ducal “credenze”, to the extent that these majolica “di terre vulgari, di non vulgare artifizio” (from vulgar lands, but not vulgar in ability) from then on achieve the status of material worthy of “a diletto e pompa dei principi” (the delight and the pomp of princes) and stand out in the first Italian majolica collection as “oggetti della meraviglia degli occhi più erudite” (objects for the astonishment of the most erudite eyes).

At the same time of the Marches district, also the one from Romagna was looking for its affirmation. Faenza is the leader, and from decades now, is a specialized centre in the production of majolica. Faenza is not a Court, so it relies on its Cento Pacifici and on the innate inclination of the mercantile activities to be able to propose “di qua et là per l’Italia” (here and there in Italy) and in Europe its majolica.

From 1530s, Faenza workshops try to compete with the Marches ones with their very refined “vaghezze” (vagueness) and “gentilezze” (graces) painted on light blue berettino enamel, framing the blazoned services with the arms of Gonzaga, Este, Pio da Carpi Guicciardini-Salviati, and so on, even if the supremacy up to mid-16th century is still in the hands of the craftsman of Marches districts. Its workshops, melting pot of experimentations, fully interpret the widespread desire of novelty thanks to a lively, immediate painting, made with few chromatic touches (deep blue, yellow, orange) on the surface now “bianche e polite” (white and clean) of a technically perfect enamel. It is a unique style, a successful novelty, in which mannerist inflexions and baroque attitudes lively become part of the rediscovered taste of making majolica: the figure scene, the allegory, the heraldic theme, themes always recurring in majolica making inspiration, acquire importance in the freedom of a new Compendiario style, as per the classical Pompeian memory.

The circle of potential clients for parade services, often with the arm, besides the princely tables, increased thanks to the anoblissement of families whose origin was mercantile or bourgeois, that liked also the white, the predominant colour, which enhanced the shapes, sometimes wavy and hull shaped, also defined as “smartellate” (hummered) or “abborchiate” (studded), especially “cavate dagli argenti” (from the silvers) e that met the most updated trends.

Heraldic study of the “whites” of Faenza described a picture of continuous trading, a lively network of families and marriage relationships as well as relationships with Church high hierarchies that played an essential role in the economic fortune of the majolica from Faenza.

So, monumental “credenze” were made with these “whites”; these soon entered in competition with the polychrome storiated ones from Urbino, in which the most organized and important workshops from Faenza excelled: those from Francesco Mezzarisa, Virgilotto Calamelli, from the Bettisis and Utilis, who, thanks to the “whites” gave life to a wide movement that renovated the Renaissance tradition that was on the decline.

Among the first clients there were the noble local families who were active and steady intermediary for improving relationships beyond their territory – at the beginning oriented towards the near rich centre of Bologna – rapidly extended to the whole region, from Parma to Rimini therefore to all the Italian aristocracy: Gonzaga, Este, Medici, Farnese, Orsini, Aldobrandini, Pallavicini, Altieri, and so on.

A flask with Malipiero coat of arms (figg. 4a, b), marked in its unmistakable heraldic figure shown through the coats of arms “d’armi e d’insegne” (of arms and insignia) of the time (fig. 4b), testifies for example how, in the second half of 16th century, Venetian nobles, even they had magnificent polychrome storiated majolica made by the productive local workshop of master Domenico, also appreciated the white “credenze” from Faenza.

The flask shows on sides two modelled harpies, whose outstretched heads offer sufficient thickness to host the hole for the rope. So, it pertains to the so-called genre “da pellegrino” (pilgrim style), a style that in the shaped surface fits to the embossed silver or copper models; a plastic effect that to some extent is absorbed by the waxy and coating quality of the enamel of the “white” from Faenza, very appealing to the touch. This style is also certified in models featured by prestigious coats of arms painted on both sides, among which, it is worth remembering the flasks for the service of Albert V of Bavaria, made around 1576 by the Bettisis workshop and for the most part housed in the Residenz Museum in Munich. Flasks featured by screw stoppers, such as this one for the Malipieros, or, just mentioning Piccolopasso with the “bocca a vite ad uso delle fiasche di argento” (screw mouth in use for the silver flasks) (fig. 4c), that the workshop itself includes also in the prestigious “credenze” for the Medici and Gonzaga families.

In transalpine countries, the Wittelsbachs are the privileged clients of the Bettisis from Faenza, and for them, in 1590, two services delivered to “the Duke of Bavaria” are reported. The Duke was Wilhelm V, who certainly was familiar and appreciated Italian majolica, having received as a gift from the Duke of Urbino, Francesco Maria della Rovere, a “credenza” made by the Fontana, the most important workshop in Urbino.

These prestigious Bavarian orders opened the way to this workshop to other wealthy commissions, especially in the South of Germany. A large bowl (figg. 5a, b) modelled in “baccellature” according to the silvers style, called “a gran costole” (large ribs), dateable to 1575–1580, was chosen to celebrate another family in the same region, the Unterholzer. Their coat of arms, decorated with lambrequins and two flashy half wings, stands out in the centre of a decoration featured by a delicate and lively ductus compendiario; the presence of two rhomboidal medallions that contain one feminine bust and one masculine bust, arranged according the “old style”, suggest the idea of a nuptial gift, seemingly confirmed by the presence of two allegorical figures, the Fortress and, perhaps, also the Prudence. Most probably it was about a supply that included also the majolica in different styles, given the existence of a flask of the already mentioned style “da pellegrino” (fig. 5c), on which the same coat of arm of the noble Bavarian family is painted.

The culture of the “whites” from Faenza, especially in the shapes of majolica, fully and lively understands the passage from Mannerism to Baroque, as per the opulent structure of its shapes, often embossed, in a plastic role of the modelled parts, accessory to the object functionality, with sphinxes, caryatids, harpies, putti, leonine or caprine legs and so on, made through plaster moulds, according to the criteria of pre-industrial serial reproducibility.

In this way, the small town from Romagna was able to tie forever its name to the fortune of its majolica and, for a century and a half, in the western world the combination Faenza-faïence ruled, up to the appearance of the European porcelain in the early 18th century. But the fortune of these works in majolica will go on thanks to the masterpieces produced by “these manufactures, since then, spread out all around Europe”, that luckily survived to the present day and that “can be admired in the private room as marvels of art”: a matter that opens on the great and fascinating theme of collecting Italian majolica, that in the future will deserve other pages of analysis.

Acknowledgments

Materials and information were generously given by: Giovanni Asioli Martini, Paolo Baccherini, Enrico Caviglia, Silvia Glaser, Johanna Lessmann, Gustav Pfeifer.

Notice

Works at figs. 2 and 5 are further developed in an essay for the catalogue of the exhibition “Prima del Made in Italy” (Before Made in Italy), in press.