Antonella Rathschüler

In Genoa, entering in a notary’s office, in the waiting room of a doctor’s office, in the living room of an elegant apartment, in the Audience Hall of the Royal Palace or during the exhibition of an auction house you can come across a cabinet by Peters, the English cabinetmaker who left an indelible mark in the 19th-century taste of Genoa…

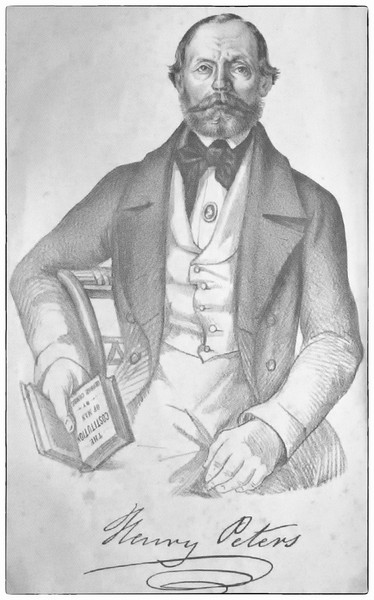

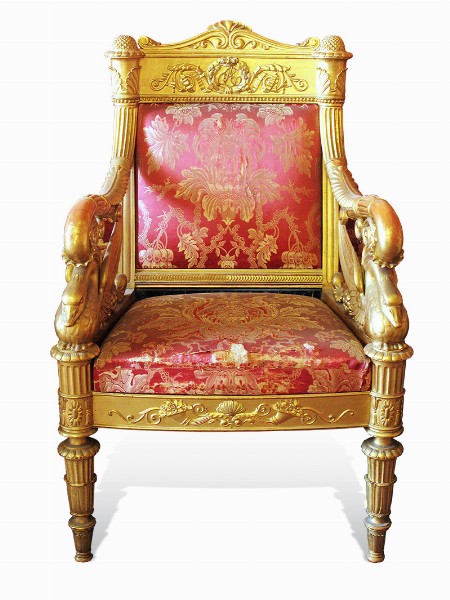

But, who is Peters? Writing on Henry Thomas Peters, in fact, does not mean to speak exclusively about a 19th-century cabinetmaker and his production, but to discover also a versatile, complex, quirky man, someone combining many aspects of a rather varied and innovative century. Dedicating a monograph to him means, first of all, telling the story of one of the many English-speaking entrepreneurs arrived on the coasts of the Italian peninsula to set up their own factories; therefore, it means to speak about the industrial development that Liguria saw between 1810 and 1820, when Genoa and Savona became one of the first industrial centres in northern Italy. Writing about Peters means also to tell the intriguing story of a cabinetmaker that left a packet of papers in which he does not speak about cabinet making, but about freedom, justice and corruption. It means speaking about a person who had relationships with Mazzini, who won Carlo Alberto of Savoy favour and was loved by most of the city nobility. A person who, as noted by the Rebaudi, “was leading with his family a princely life; was maniac for horses; had luxurious Parisians, and was frequently seen walking at Acquasola, where he drove rich chariots with two and four horses.” There is a halo around Peters, making him a well-known figure in Genoa more than any other skilled cabinetmaker. Most of the antique dealers, historians and art historians know something about him: that he went to prison, that “he was a spendthrift”, that he was a supporter of Mazzini, that he died in abject poverty; many information partially real, but that were not fully documented until yesterday. These vague news, this talking and “badmouthing” around someone who died over a hundred years ago, convinced me to shed a bit of light on the subject, looking for the documentation on which so many information relied on. Up to now, Peters has been a subject chronologically too close to our time to be considered from an historical point of view and then studied in a scientific way, and too far away to have clear oral information about him. Furthermore, for almost one century, his production has not received the due attention, as well as the entire 19th-century production that began to be protected in a rational way only a few decades ago.Peters’ furniture was not considered as a showpiece, and the dispersion of the furnishings he created is huge. Trying to make a work of reorganization, my study was based on the reading of the documents signed between Peters and his clients (contracts, payments, terms and conditions) and on the analysis of some furnishings he made for the Royal Palace and the Red Palace of Genoa, for the castles of Racconigi and Pollenzo, and for Villa Faraggiana in Albissola, investigating only on the most famous depositing and discarding the furnishings that could not be documented (for lack of brand or written testimony).But a versatile person as Peters forced me to dwell not only on the analysis of his production. His writings, his letters, his pleas forced me to follow different tracks and to investigate with curiosity the “Peters’ case”, reconstructing, as far as possible, his complex biography.In Peters’ life there are still many unknown sides, as the period he spent in England up to his twenty-four years old, or the reason why he moved to Italy and why he choose Genoa as a place of business.There are also some dark sides, both in his almost immediate rise to popularity and in the sudden fall, up to bankruptcy, imprisonment, and his death.To order all the material I found (documents and furniture production), I divided the text into two parts: the first one contains an introduction to the man and an analysis of his production, his techniques, his style; the second one, a study, through a wide documentation, of his most important furniture, mostly housed in public collections. In conclusion, I think it can be said that Peters’ originality is not in the stylistic features, that reflect the most popular models in France and in England at the time, but in the introduction of industrial processes in the Genoese art of cabinetmaking, in his new way of dealing with the public, in the fully entrepreneurial character of his activity and, above all, in the most refined technical quality ever achieved by any cabinetmaker imitating his art.

In Genoa, entering in a notary’s office, in the waiting room of a doctor’s office, in the living room of an elegant apartment, in the Audience Hall of the Royal Palace or during the exhibition of an auction house you can come across a cabinet by Peters, the English cabinetmaker who left an indelible mark in the 19th-century taste of Genoa…

But, who is Peters? Writing on Henry Thomas Peters, in fact, does not mean to speak exclusively about a 19th-century cabinetmaker and his production, but to discover also a versatile, complex, quirky man, someone combining many aspects of a rather varied and innovative century. Dedicating a monograph to him means, first of all, telling the story of one of the many English-speaking entrepreneurs arrived on the coasts of the Italian peninsula to set up their own factories; therefore, it means to speak about the industrial development that Liguria saw between 1810 and 1820, when Genoa and Savona became one of the first industrial centres in northern Italy. Writing about Peters means also to tell the intriguing story of a cabinetmaker that left a packet of papers in which he does not speak about cabinet making, but about freedom, justice and corruption. It means speaking about a person who had relationships with Mazzini, who won Carlo Alberto of Savoy favour and was loved by most of the city nobility. A person who, as noted by the Rebaudi, “was leading with his family a princely life; was maniac for horses; had luxurious Parisians, and was frequently seen walking at Acquasola, where he drove rich chariots with two and four horses.” There is a halo around Peters, making him a well-known figure in Genoa more than any other skilled cabinetmaker. Most of the antique dealers, historians and art historians know something about him: that he went to prison, that “he was a spendthrift”, that he was a supporter of Mazzini, that he died in abject poverty; many information partially real, but that were not fully documented until yesterday. These vague news, this talking and “badmouthing” around someone who died over a hundred years ago, convinced me to shed a bit of light on the subject, looking for the documentation on which so many information relied on. Up to now, Peters has been a subject chronologically too close to our time to be considered from an historical point of view and then studied in a scientific way, and too far away to have clear oral information about him. Furthermore, for almost one century, his production has not received the due attention, as well as the entire 19th-century production that began to be protected in a rational way only a few decades ago.Peters’ furniture was not considered as a showpiece, and the dispersion of the furnishings he created is huge. Trying to make a work of reorganization, my study was based on the reading of the documents signed between Peters and his clients (contracts, payments, terms and conditions) and on the analysis of some furnishings he made for the Royal Palace and the Red Palace of Genoa, for the castles of Racconigi and Pollenzo, and for Villa Faraggiana in Albissola, investigating only on the most famous depositing and discarding the furnishings that could not be documented (for lack of brand or written testimony).But a versatile person as Peters forced me to dwell not only on the analysis of his production. His writings, his letters, his pleas forced me to follow different tracks and to investigate with curiosity the “Peters’ case”, reconstructing, as far as possible, his complex biography.In Peters’ life there are still many unknown sides, as the period he spent in England up to his twenty-four years old, or the reason why he moved to Italy and why he choose Genoa as a place of business.There are also some dark sides, both in his almost immediate rise to popularity and in the sudden fall, up to bankruptcy, imprisonment, and his death.To order all the material I found (documents and furniture production), I divided the text into two parts: the first one contains an introduction to the man and an analysis of his production, his techniques, his style; the second one, a study, through a wide documentation, of his most important furniture, mostly housed in public collections. In conclusion, I think it can be said that Peters’ originality is not in the stylistic features, that reflect the most popular models in France and in England at the time, but in the introduction of industrial processes in the Genoese art of cabinetmaking, in his new way of dealing with the public, in the fully entrepreneurial character of his activity and, above all, in the most refined technical quality ever achieved by any cabinetmaker imitating his art.