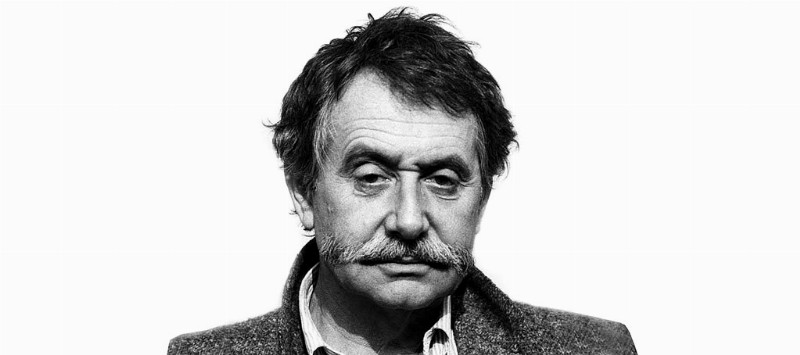

Andrea Pietro Mori

Fed by fashion magazines and ancient civilizations, unaware – despite his Austrian origins – to the functionalist lesson of Bauhaus and Ulm school, Sottsass forms his idea of design starting from the rejection for the amoral architecture of the plan Ina-Casa, supported by the rationalist movement of the post-war period. Artist, painter of the MAC (Concrete Art Movement) group and photographer, the architect from Innsbruck indicates a new way to be a designer – free from the design office – and becomes a true actor of visual culture. At the outset of the electronic era, he designs, for Adriano Olivetti, the first Elea calculator, followed by the famous Valentine typewriter, winning the Compasso d’Oro: these are objects in which shape has a “psychic function.” The interpretation of the contact between oriental spirituality and occidental materialism appears in the beat magazine “Pianeta fresco” (set up in 1967 with Allen Ginsberg and his wife Fernanda Pivano), in the ceramics for Bitossi and in the experimental furniture for Poltronova, created to catalyse cultural energies or stimulate new domestic behaviours. In those years, being part of his wife’s cultural circle, he met the American cultural environment. He met important classical writers – Hemingway, Faulkner, Scott Fitzgerald –, young exponents of beat generation, such as Kerouac and Bukowski; they all shared the criticism towards society and towards the capitalism of advertising and consumerism, and the freshness and dynamism of ideas. On the contrary, he did not share their pessimistic and resigned approach, nor their lifestyle. Anticipating the years of protests, he indicated design as an instrument of criticism, giving life to Radical Design season (1966–1972) and stating the need of a new aesthetics, more ethical, social and political. Disappointed by an insatiable industry, Sottsass planned the union of the avant-garde suggestions with the idea of a “calming” design, as expression of an alternative consumerism. The apex of this research is Italy: The New Domestic Landscape (1972), an exhibition at MoMA in which the Micro Environment, futuristic and grey “environment house,” wants to “neutralise” a culture based on the standards of a rationalism that finds in the consumerism the irrational factor that can invalidate the project. The restlessness is expressed also in the famous Design Metaphors (1972–1974), outdoor installations that look for an authentic relationship between uncontaminated nature and the order of a theatrical and poetic interior design. The drawings of Il Pianeta come Festival, the counter-school of free creativity Global Tools (set up with Archizoom and Superstudio), and some memorable Triennial Exhibitions complete an intense season which made him famous worldwide, and had him invited to the Biennial Exhibition in Venice in 1976. Continuously looking for experiences, he travelled frequently to ancient and spiritual countries, he dedicated to a new group, Alchimia, and engaged himself in exhibitions closing the radical season. With the need to start a production, emphasizing the linguistic research, the group of artists, film directors and architects under the Manifesto per lo sviluppo del disegno come pensiero (Manifest for the development of design as thought) created “infinite” furniture to tell emotions and feelings. Sottsass triggers an alchemy of shapes, rhythms, colours and materials, which revolutionised the aesthetic standards and the way to conceive design against decoration.From this to New Design it’s a short step, undertaken by Sottsass in 1981 setting up the Memphis group, together with Hans Hollein, Arata Isozaky, Andrea Branzi, Michele de Lucchi and other important architects, who changed the features of modern furniture. Memphis gave the objects a symbolic, emotional and ritual substance. It is based on “the emotion before the function.” This is the case of the Carlton bookcase, a halfway through a totem and a video game. Industry and market well received the intelligent challenge, therefore Sottsass set up, with young and unknown followers, the Sottsass Associati atelier. Casa Wolf, Casa Olabuenaga, Casa Cei, Casa Bischofberger, the Museo dell’Arredo Contemporaneo in Ravenna, Casa degli Uccelli, are some of the examples of design aimed at putting in systematic contact nature and construction, following the ideal of farmers’ wisdom and interpreting the rules of the genius loci. Differently from Deconstructionism, an intellectual game of decompositions, Sottsass’ architecture corresponds to the pulsing of vital functions. His main work confirms it; Malpensa 2000 is a place made of non-glaring and soundproof materials, natural colours and linear designs. A place representing the calm Mediterranean identity and communicating the idea of an Italy “not stressed, not pretentious but dedicated to a culture of mankind.” An airport as a space-pause of meditation rather than a place of cold celebration of the hyper-technological, fast and stressful societies. Sottsass testifies a path made of internal revolutions, but also of devotion to his neoplastic heritage, to the use of essential and archetypal shapes. Sottsass’ way of thinking through shapes does not follow absolute laws, but emotional and cognitive processes, deeply human. In a society that “plans obsolescence,” his design gives back the image of the society and stimulates the recovery of the ethical function of the industry. The formal quality of everyday life is for him a political issue. “If something will save us, it will be the beauty,” he wrote, at 85, to conclude his Scritti (Writings).And we can believe to someone who lived his life as an open work of art, distilled by an restless intelligence in drops of calm and joyful design.

I wonder why

“...My opinion is that [...] the problem is not to get close to ‘good design’ but to do design, to get as close as possible to an anthropologic state of things, that must be as close as possible to the need that the society has of its self-image. If it is true that we live in a society planning obsolescence, the only design that can last is the one that has something to do with obsolescence, a design which fits it, maybe speeding it up, maybe confronting it, maybe laughing at it, maybe getting on well with it. The only design that cannot last is the one that in a society planning obsolescence, looks for metaphysics, the absolute and eternity. And then, I don’t understand why the design which lasts might be better than the one that disappears. I don’t understand why stones must be better than the feather of a bird-of-paradise. I don’t understand why pyramids are better than Burmese thatched huts. I don’t understand why the speeches of the president are better than the love words whispered in a bedroom at night. When I was young, I collected information only from fashion magazines or from very ancient civilizations, forgotten, destroyed, dusty. I collected information from the areas in which life is arising, or from the nostalgia for life, but never from institutions, never from solidity, never from reality, never from crystallization, never from hibernation. For me, obsolescence is the ‘sugar of life’.”

Ettore Sottsass’ design is not limited by the need to shape a product addressed to industry; it must teach something about itself, it must communicate something on life, explaining that technology too is one of its metaphors.

Fed by fashion magazines and ancient civilizations, unaware – despite his Austrian origins – to the functionalist lesson of Bauhaus and Ulm school, Sottsass forms his idea of design starting from the rejection for the amoral architecture of the plan Ina-Casa, supported by the rationalist movement of the post-war period. Artist, painter of the MAC (Concrete Art Movement) group and photographer, the architect from Innsbruck indicates a new way to be a designer – free from the design office – and becomes a true actor of visual culture. At the outset of the electronic era, he designs, for Adriano Olivetti, the first Elea calculator, followed by the famous Valentine typewriter, winning the Compasso d’Oro: these are objects in which shape has a “psychic function.” The interpretation of the contact between oriental spirituality and occidental materialism appears in the beat magazine “Pianeta fresco” (set up in 1967 with Allen Ginsberg and his wife Fernanda Pivano), in the ceramics for Bitossi and in the experimental furniture for Poltronova, created to catalyse cultural energies or stimulate new domestic behaviours. In those years, being part of his wife’s cultural circle, he met the American cultural environment. He met important classical writers – Hemingway, Faulkner, Scott Fitzgerald –, young exponents of beat generation, such as Kerouac and Bukowski; they all shared the criticism towards society and towards the capitalism of advertising and consumerism, and the freshness and dynamism of ideas. On the contrary, he did not share their pessimistic and resigned approach, nor their lifestyle. Anticipating the years of protests, he indicated design as an instrument of criticism, giving life to Radical Design season (1966–1972) and stating the need of a new aesthetics, more ethical, social and political. Disappointed by an insatiable industry, Sottsass planned the union of the avant-garde suggestions with the idea of a “calming” design, as expression of an alternative consumerism. The apex of this research is Italy: The New Domestic Landscape (1972), an exhibition at MoMA in which the Micro Environment, futuristic and grey “environment house,” wants to “neutralise” a culture based on the standards of a rationalism that finds in the consumerism the irrational factor that can invalidate the project. The restlessness is expressed also in the famous Design Metaphors (1972–1974), outdoor installations that look for an authentic relationship between uncontaminated nature and the order of a theatrical and poetic interior design. The drawings of Il Pianeta come Festival, the counter-school of free creativity Global Tools (set up with Archizoom and Superstudio), and some memorable Triennial Exhibitions complete an intense season which made him famous worldwide, and had him invited to the Biennial Exhibition in Venice in 1976. Continuously looking for experiences, he travelled frequently to ancient and spiritual countries, he dedicated to a new group, Alchimia, and engaged himself in exhibitions closing the radical season. With the need to start a production, emphasizing the linguistic research, the group of artists, film directors and architects under the Manifesto per lo sviluppo del disegno come pensiero (Manifest for the development of design as thought) created “infinite” furniture to tell emotions and feelings. Sottsass triggers an alchemy of shapes, rhythms, colours and materials, which revolutionised the aesthetic standards and the way to conceive design against decoration.From this to New Design it’s a short step, undertaken by Sottsass in 1981 setting up the Memphis group, together with Hans Hollein, Arata Isozaky, Andrea Branzi, Michele de Lucchi and other important architects, who changed the features of modern furniture. Memphis gave the objects a symbolic, emotional and ritual substance. It is based on “the emotion before the function.” This is the case of the Carlton bookcase, a halfway through a totem and a video game. Industry and market well received the intelligent challenge, therefore Sottsass set up, with young and unknown followers, the Sottsass Associati atelier. Casa Wolf, Casa Olabuenaga, Casa Cei, Casa Bischofberger, the Museo dell’Arredo Contemporaneo in Ravenna, Casa degli Uccelli, are some of the examples of design aimed at putting in systematic contact nature and construction, following the ideal of farmers’ wisdom and interpreting the rules of the genius loci. Differently from Deconstructionism, an intellectual game of decompositions, Sottsass’ architecture corresponds to the pulsing of vital functions. His main work confirms it; Malpensa 2000 is a place made of non-glaring and soundproof materials, natural colours and linear designs. A place representing the calm Mediterranean identity and communicating the idea of an Italy “not stressed, not pretentious but dedicated to a culture of mankind.” An airport as a space-pause of meditation rather than a place of cold celebration of the hyper-technological, fast and stressful societies. Sottsass testifies a path made of internal revolutions, but also of devotion to his neoplastic heritage, to the use of essential and archetypal shapes. Sottsass’ way of thinking through shapes does not follow absolute laws, but emotional and cognitive processes, deeply human. In a society that “plans obsolescence,” his design gives back the image of the society and stimulates the recovery of the ethical function of the industry. The formal quality of everyday life is for him a political issue. “If something will save us, it will be the beauty,” he wrote, at 85, to conclude his Scritti (Writings).And we can believe to someone who lived his life as an open work of art, distilled by an restless intelligence in drops of calm and joyful design.

I wonder why

“...My opinion is that [...] the problem is not to get close to ‘good design’ but to do design, to get as close as possible to an anthropologic state of things, that must be as close as possible to the need that the society has of its self-image. If it is true that we live in a society planning obsolescence, the only design that can last is the one that has something to do with obsolescence, a design which fits it, maybe speeding it up, maybe confronting it, maybe laughing at it, maybe getting on well with it. The only design that cannot last is the one that in a society planning obsolescence, looks for metaphysics, the absolute and eternity. And then, I don’t understand why the design which lasts might be better than the one that disappears. I don’t understand why stones must be better than the feather of a bird-of-paradise. I don’t understand why pyramids are better than Burmese thatched huts. I don’t understand why the speeches of the president are better than the love words whispered in a bedroom at night. When I was young, I collected information only from fashion magazines or from very ancient civilizations, forgotten, destroyed, dusty. I collected information from the areas in which life is arising, or from the nostalgia for life, but never from institutions, never from solidity, never from reality, never from crystallization, never from hibernation. For me, obsolescence is the ‘sugar of life’.”

Ettore Sottsass’ design is not limited by the need to shape a product addressed to industry; it must teach something about itself, it must communicate something on life, explaining that technology too is one of its metaphors.